I claim this land and all its riches

Patent law aims to promote the publication of technical advances so that duplicative work is avoided. Patents offer inventors an exclusive right to their invention (for a limited time in a limited geographical area) in exchange for publication.

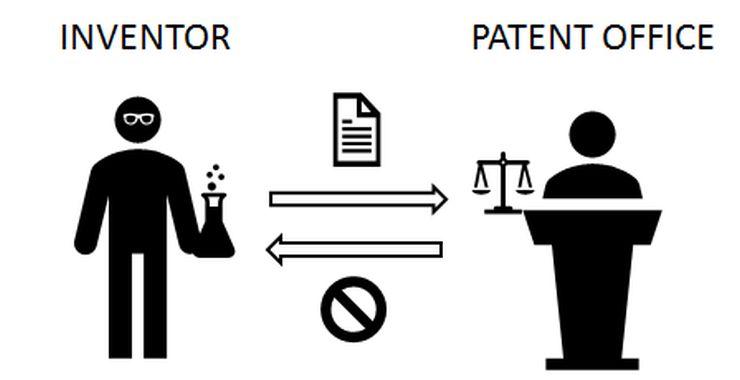

But before obtaining a patent, an inventor must present the invention in a written application which is submitted to a patent office. The application must include a patent claim which specifies the extent of the exclusive right which the inventor seeks to be rewarded. A patent claim has to be made in writing and the words in the claim should define the invention in precise terms, so that (if the patent office grants the claim) all interested parties can determine which devices this exclusive right covers, and which ones it doesn’t cover.

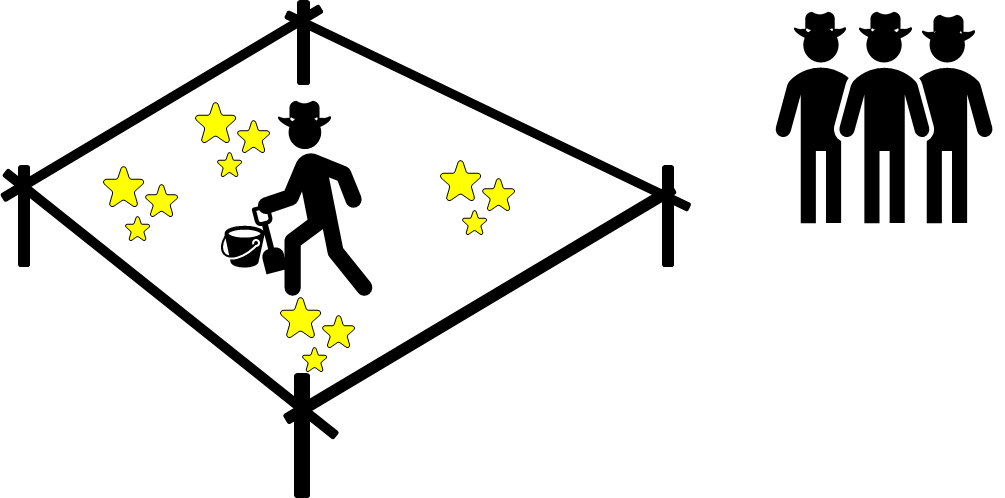

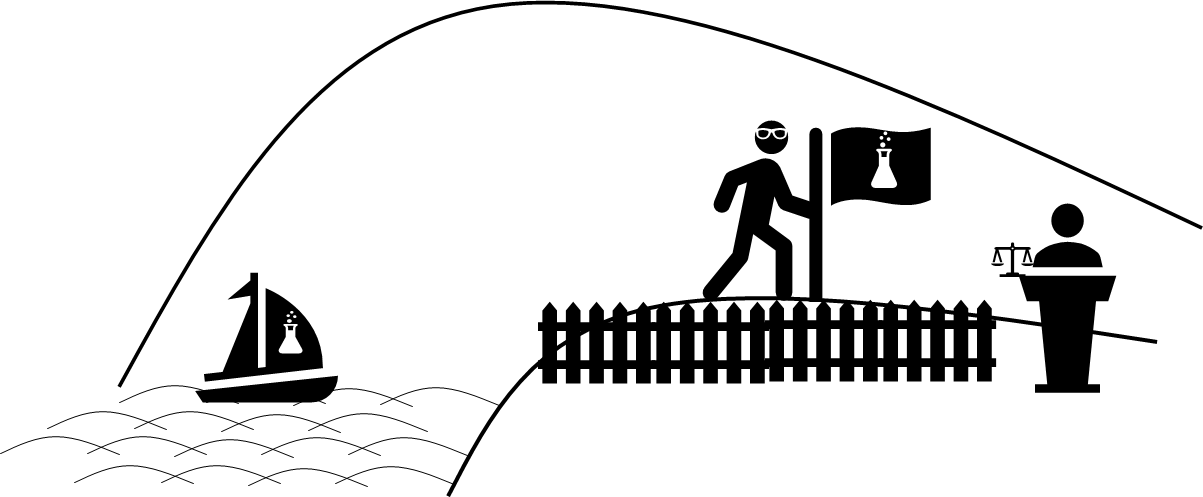

Patent claims are reminiscent of land claims in that they require fair rules. In the California Gold Rush of in the mid-1800s, gold prospectors could make land claims in their own name when exploring the wilderness. The first person to discover a gold deposit could claim the area around the deposit as their own. That claim was recorded in a public register, and the person in question then had the right to exclude others from digging within the claimed area. A land claim was valid if the land had not been fenced in before, but one person could only claim a fairly restricted area. It would have been against the public interest for one person to be awarded an exclusive right to a vast area.

In much the same way, patent claims are usually not granted in very broad form, because an exclusive right is a monopoly right which can limit competition and development. It is therefore in the public interest that granted patent claims should be fairly restricted. Patent offices therefore apply certain criteria for judging whether a claim can be granted or not.

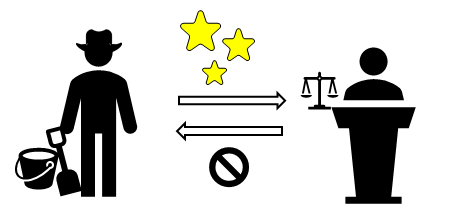

The first patent criterion is similar to the criterion of unfenced land in the Gold Rush. In other words, a patent is valid if nobody has discovered the same invention before. However, the crucial criterion for a patent claim is not if someone has previously submitted a patent application for the same invention, but whether or not the same invention has been published before. This publication could be an earlier patent application, but it could also be any other form of written publication.

So in Gold Rush terms, this novelty criterion would have stated that a gold prospector could not have a legal claim to a certain piece land if someone had previously published the information that there was gold beneath that land. If someone discovered an area laden with gold, but published the discovery in the local paper without making a claim, then that land would immediately been turned into a public domain, which could no longer be claimed for personal use. It would therefore have been a foolish mistake to publicize information about a new gold deposit before staking a claim.

The reason for this strict novelty criterion in patent law is that nobody should obtain an exclusive right to an invention simply by copying information which is already known. Exclusive rights are reserved only for those who do the actual digging, as long as they remember to claim their discoveries before publicizing them.

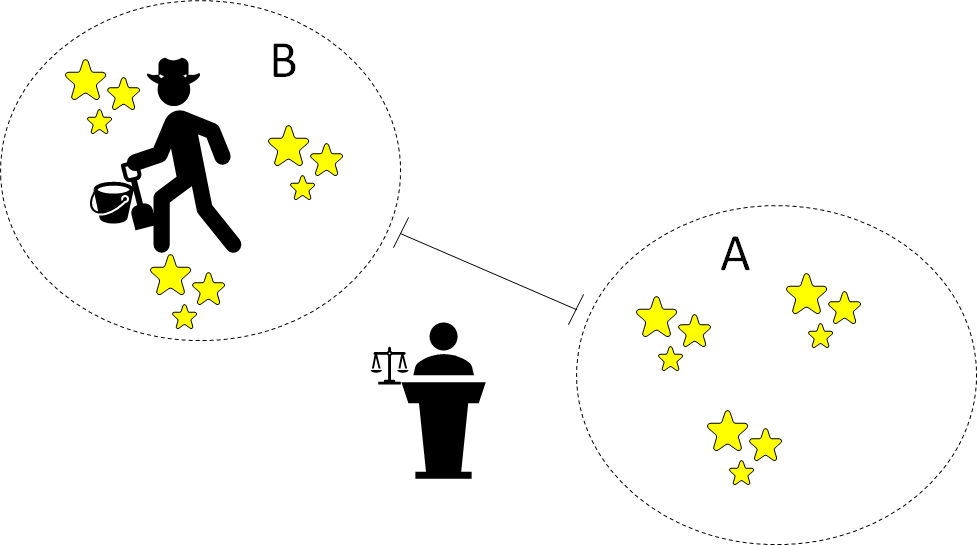

Patent claims also have to meet the criterion of inventive step. In Gold Rush terms, this criterion would have stated that a certain gold deposit can only be legally claimed if it lies beyond a certain minimum distance from all the other gold deposits which have hitherto been publicized. In other words, if it was already publicly known that area A contained a gold deposit, then a gold prospector may not have been allowed to claim the immediately adjacent area B for himself. The distance between the areas could have been considered so short that it would have been obvious to the average gold prospector that there must be gold under area B as well. It could therefore not be claimed by anyone.

This criterion seems quite unfair for a gold prospector. The reason why this criterion is necessary in patenting is simply that the number of granted patents should obtain. The number of small modifications which can be made to one previously published device is almost limitless, so patent rights cannot be granted to insignificant improvements. Patent offices therefore demand that a claim must take an “inventive step” over a previous discovery. This criterion can sometimes be tough on inventors who find gold in area B without being aware of the adjacent gold deposit in A which had been previously reported.

Another criterion which patent claims and land claims share is that they should not be speculative to an unfair degree. Inventors performing cutting-edge research can sometimes form educated guesses on how new materials or methods could be used in the future. But it is important for a well-functioning patent system that pure guesswork isn’t rewarded with an exclusive right. The criterion of sufficient disclosure therefore demands that the patent application must provide enough concrete evidence to show that a patent claim is not speculative.

In Gold Rush terms, this criterion would have demanded that a gold prospector had to provide solid proof when claiming a new gold deposit, and his claim had to be limited only to that deposit. He could not claim larger tracts of land just by speculating that they might contain gold as well. Those lands had to be left open for other prospectors to dig into.

Finally, patent claims also have to meet a clarity criterion. Interpreting a patent claim is generally a lot more difficult than checking a land claim because many different words and expressions can be used to describe the same technical device. It is not always easy to say whether or not an apparatus used by a competitor actually corresponds to the definitions of a patent claim.

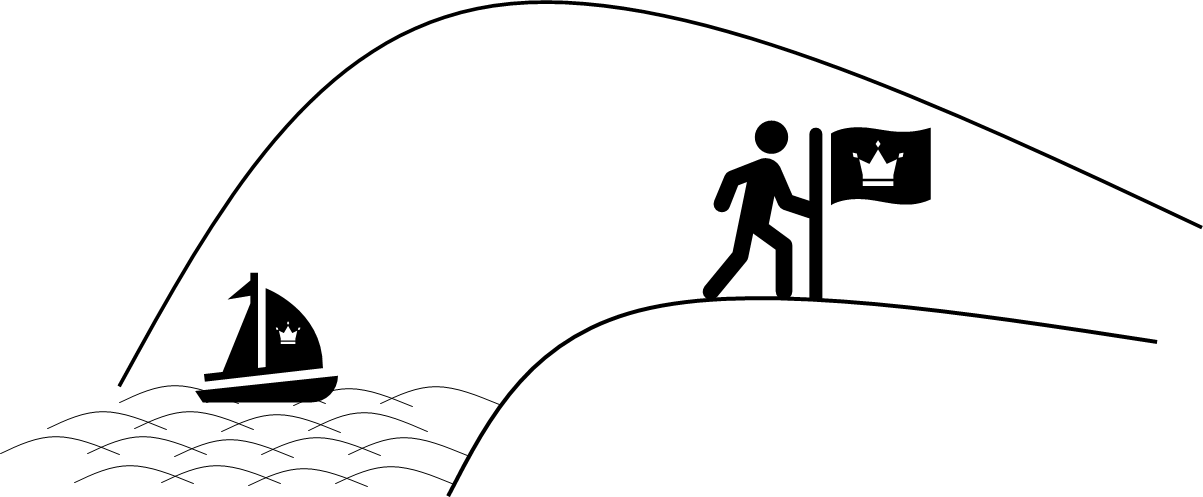

Some adventurous inventors try to benefit from this linguistic ambiguity by trying to claim patent rights in deliberately unclear or vague language. If they manage to get the claim granted, its scope may (under some interpretations) be much broader than the actual invention really warrants. Claims like this resemble the land claims made by conquistadors who ceremonially claimed the entire American continent in the name of their queen when stepping ashore from their ships.

Since such overreaching claims are unreasonable and harmful to the public interest, patent offices judge the clarity of patent claims very strictly. Even if no previously published devices come close a claimed invention, a claim may still be rejected for lack of clarity if the technical terms used in the claim are ambiguous.

Ambiguity is to some extent a matter of opinion. People from different research communities may disagree about the exact meaning of a term, especially in international contexts where patent claims are translated from one language to another. To reduce the likelihood of clarity objections and disagreement, it is advisable to include in every patent application a dictionary section where the meaning of key technical terms is elaborated.

This dictionary section can serve as a fence when the inventor arrives on a new continent. The patent office will check that the claim is demarcated with exact technical definitions. With the help of his dictionary, the inventor can put up a fence which clearly indicates which areas have been claimed and which ones still remain unexplored. If the inventor did not bring along the necessary fencing materials on his ship, the patent office may force him to return home empty-handed due to the lack of clarity in his claim.

Uusimmat blogiartikkelit

Kolme bocolaista nimitetty Markkinaoikeuden asiantuntijajäseniksi

Essi Karppanen, Saoussen Merdes ja Anastasiia Kravtcova suorittaneet vaativan EQE:n ensimmäisen vaiheen

Market Explorer -rahoituksella tukea PK- ja midcap yrityksille

Boco IP yksi Suomen parhaista työpaikoista Great Place To Work® -listalla

Vanteista vahinkoihin: suomalaisen maahantuojan oppitunti tavaramerkkioikeuksista

Esittelyssä Boco IP:n Essi Karppanen

Kirjoittaja