Coming soon: The European Unitary Patent

The unitary patent is coming soon. But what is it actually? The European patent system will undergo a significant change in 2023. When the European Patent Office (EPO) grants an application, the applicant can choose to receive a unitary patent which covers multiple countries. A Unified Patent Court (UPC) is about to be instituted this year, and it will have jurisdiction in all disputes which relate to unitary patents. Even disputes relating to old European patents may in some cases be resolved by the Unified Patent Court unless the proprietor requests an OPT-OUT from the new system. I will here explain the practical consequences of these changes for companies who own patents granted by the EPO or are currently applying for such patents.

The present system (1973 – 2022)

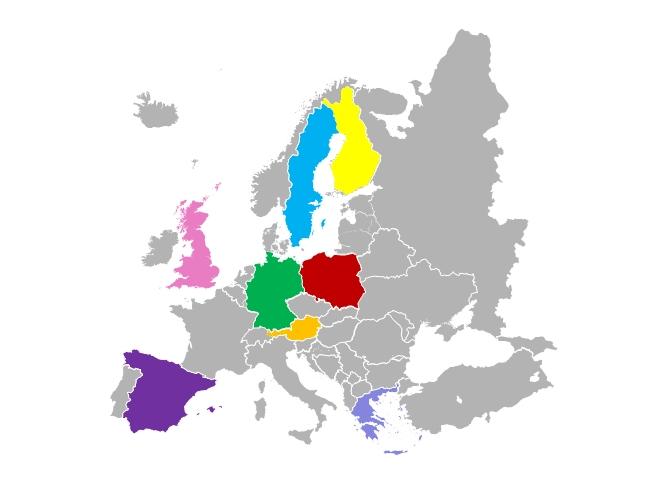

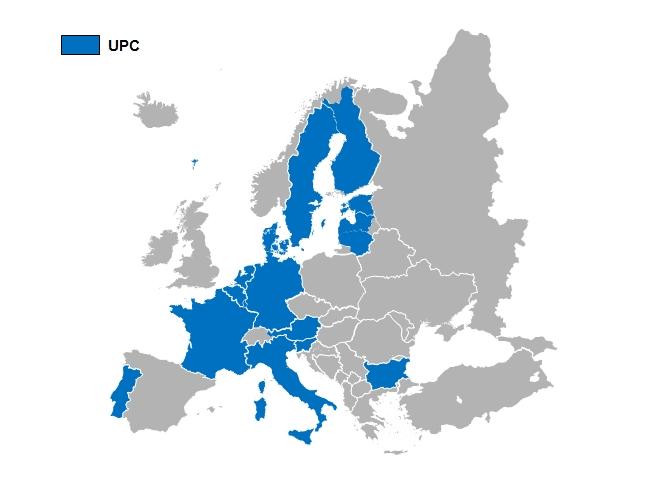

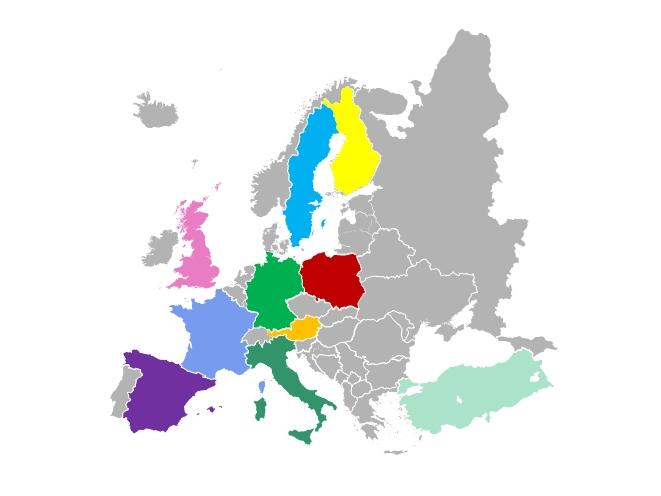

Almost all European countries have signed the European Patent Convention (EPC). These countries are marked red in figure 1. A patent right can be obtained in any of these countries by submitting a European patent application to the EPO.

The EPO examines European patent application according to the criteria set forth in the EPC and decides whether or not the application can be granted. However, when the EPO grants an application, the applicant does not automatically obtain a patent which covers all the red countries. Instead applicants must choose where they want to put in force the patent right which the EPO has granted. This process is called validation of the European patent (or EP validation). European patents are usually not validated in all red countries because every validation produces additional costs and annuities must be paid separately in each country.

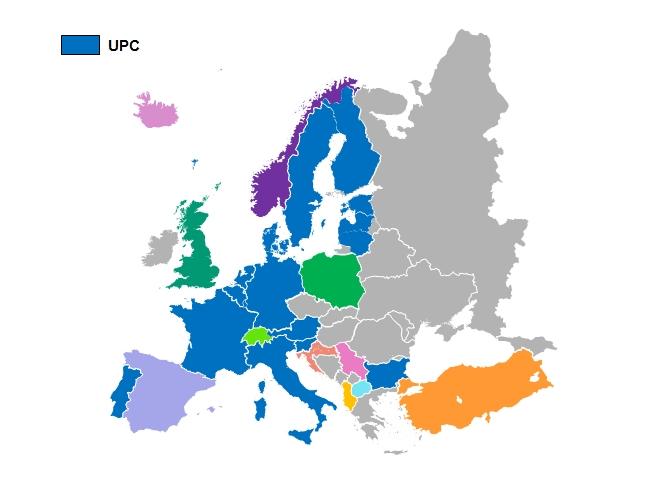

Let’s assume that an applicant validates a granted European patent in Finland, Sweden, Great Britain, Spain, Germany, Poland, Austria and Greece. The end result is illustrated in figure 2.

The applicant now owns a patent right in all EPC-countries where the European patent was validated. These rights are separate national patents and are therefore marked with different colors. These patents are not under the jurisdiction of a common European patent court (no such court exists in the present system). Instead, each national patent is under the jurisdiction of the corresponding national court.

The EU has a large internal market but the protection which can be obtained from a European patent is fragmented under a multitude of jurisdictions. If a patent right is infringed in multiple countries, the proprietor must undertake separate legal action in each country. Competitors must also file separate lawsuits in each country where they want to challenge an existing patent right. The main objective of the UPC system is to provide an improvement to this aspect of the European patent system.

The future system (probably from 2030 onwards)

It is easiest to understand the UPC system in its final form, after the transition period has ended. Presently this means the year 2030, it is possible that the system enters its final stage as late as 2037 if the transition period is extended.

In its final form the system will work like this:

- European patent applications will be examined at the EPO just as before, so the criteria by which applications are judged will not change. Furthermore, all countries shown in red in figure 1 will still participate in one form or another in the system (either as a UPC member or as a non-member). It will be possible to obtain patents in exactly the same countries as before.

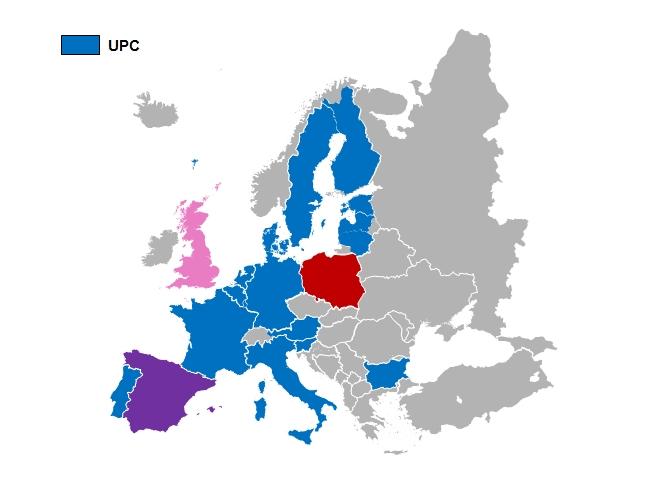

- The most important novelty is this: When the EPO grants a European patent application, the applicant can decide to put the patent in force as a unitary patent which covers all UPC-countries. The 16 countries which have to date ratified the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court are shown in blue in figure 3. Eight further countries (Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Greece, Hungary, Oreland, Malta and Romania) will hopefully also ratify the agreement within a few years. Unitary patents are always under the jurisdiction of the Unified Patent Court. Just a single lawsuit to the UPC is needed if a patent proprietor suspects that patent infringement is taking place in many blue countries. The decision given by the court will cover all UPC countries. Competitors can likewise file an invalidation lawsuit at the Unified Patent Court. If the Court considers the patent invalid, the patent right will be simultaneously revoked in all blue countries.

- When the EPO grants a European patent application, the applicant can also validate the patent in any country. This EP validation yields a national patent under national jurisdiction, just as it does in the present system. A single European patent application can thereby yield the patent family illustrated in figure 4: a unitary patent (blue countries, UPC jurisdiction) + validated national patents (other colors, national jurisdiction).

- There is no obligation to use the unitary patent. In other words, the applicant can still perform national validations in any countries and obtain the patent rights illustrated in figure 2. But double patenting will be prohibited, so selecting the unitary patent according to figure 4 closes the possibility of national validation in UPC countries.

Transition phase (2023 – probably 2030): changes for new granted EP-applications

Let’s now take a look at the transition phase which begins nest year. At the time of writing (3/2022), practical preparations are under way for starting the operations of the Unified Patent Court and it looks like the UPC agreement will come into force in the fall of 2022 or the 2023 winter. This will mark the start of the transition period, when the system will work like this:

A. When the EPO grants a European patent application, the applicant can validate the European patent in any EPC country (the red countries in figure 1). The end result of this EP validation will then be a bundle of national patents.

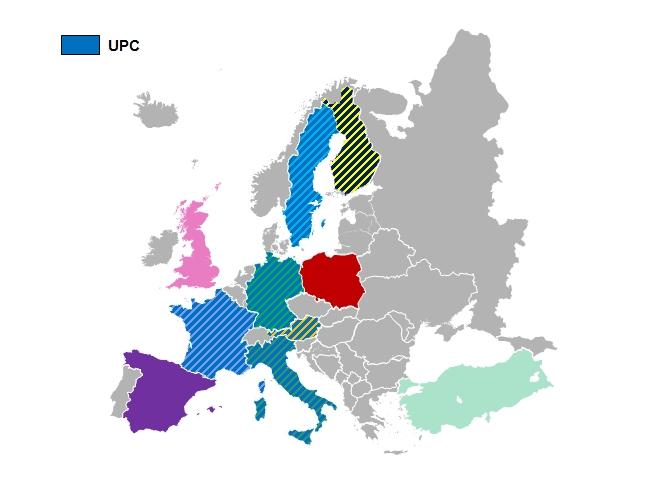

Although EP validation is performed exactly like before during the transition period, the legal status of the validated patent will be different from what it used to be in the old system. All patents which are validated in UPC countries will during the transition period by default be placed under the jurisdiction of the UPC court when the new system is operational in 2023. These patents will therefore be both under the jurisdiction of a national court and under the jurisdiction of the UPC (unless the applicant makes an UPC OPT-OUT announcement – I will say more about this below).

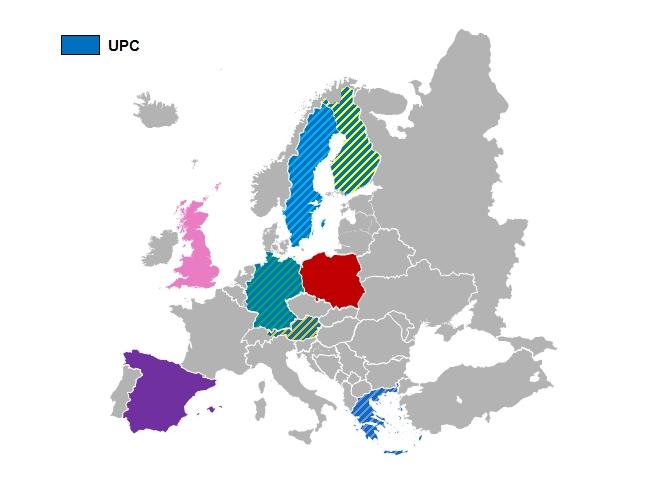

Figure 5 illustrates a patent family obtained by validating a granted European patent in the colored countries during the transition period. The applicant has performed national validations in exactly the countries as in figure 2 but has not exercised the OPT-OUT. Finland, Sweden, Germany, Austria and Greece have been marked with striped colors to illustrate that these national patents are both the jurisdiction of both the UPC and the corresponding national court. The patents in Great Britain, Spain and Poland, on the other hand, are illustrated with a single color. They will not under any circumstance be under the jurisdiction of the UPC since these countries are not UPC states. Greece is here used as an example of a country which has not yet ratified the UPC agreement but may do so in the future. The status of the Greek patent will depend on Greece’s ratification status on the day when the patent was granted: if the grant occurs after Greece has ratified the UPC agreement, then figure 5 is correct. If it occurred before Greece ratified the agreement, then the Greek patent will not be under the jurisdiction of the UPC and Greece should instead be presented with a single color in figure 5.

The proprietor of the patent family in figure 5 can file an infringement lawsuit with the Unified Patent Court if infringement takes place in any (striped) UPC-country. The decision given by the UPC will then have legal force in all striped countries. Alternatively, the owner could file separate infringement lawsuits with the national authorities in some or all of the striped countries. Correspondingly, a competitor who wants to invalidate the patent family illustrated in figure 5 can tackle this patent right in all striped UPC-countries with one UPC lawsuit, or alternatively deal with them one by one through national lawsuits. But neither the proprietor nor the competitor has any choice when it comes to Great Britain, Spain and Poland: the only way to enforce or invalidate this patent rights in non-UPC countries is to take action in national courts.

The proprietor can during the transition period remove all national patents shown in figure 5 from UPC jurisdiction by making an official OPT-OUT request. It’s possible to make the OPT-OUT request already when an application is being examined by the EPO. The OPT-OUT moves the patent family back to the status illustrated in figure 2: every national patent is only under national jurisdiction, so the proprietor and competitors can only take national legal action. Proprietors who change their mind about the OPT-OUT can return once more to the status shown in figure 5 by requesting an OPT-OUT cancellation. However, no further OPT-OUTs back to figure 2 will then be possible.

The OPT-OUT ensures that the patent proprietor will avoid situations where a competitor tries to invalidate a bundle of national patents at the Unified Patent Court. The OPT-OUT also closes the doors of the UPC for proprietors themselves, but they have the possibility of opening those doors back up by cancelling the OPT-OUT.

B. When the EPO grants a European patent application during the transition period, the applicant’s second option is to decide that the granted patent should be put in force as a unitary patent in the UPC countries. In addition to receiving the unitary patent, the applicant can also decide to validate the granted patent in non-UPC countries. The end result can then for example the patent family shown in figure 6.

No OPT-OUTs can be made in the patent family illustrated in figure 6. It is not possible to convert the unitary patent into a bundle of national applications, and the unitary patent cannot be brought under the jurisdiction of national courts in UPC countries.

It should also be noted that a unitary patent can be obtained only through a European patent application which is granted by the EPO after the UPC has come into force, when the application is granted. The patent proprietor cannot convert a bundle of national patents (figure 2 or figure 5) into a unitary patent. This is true regardless of when the application is granted (before or after the UPC start).

Consequently, as soon as the UPC is in force (and the transition period has begun), the applicant has to make decision A or B for every European patent application granted by the EPO.

Additionally, the transition period also brings along some changes for national patent rights that were created by EP-validation before 2023.

Transition phase: changes for European patents granted and validated before 2023

Let’s assume you own a large European patent family which was created many years ago by validating a European patent in the countries which have been colored in Figure 7. The present legal status of this family is shown in Figure 7 – each patent is under national jurisdiction.

Figure 8 shows the same patent family on the day when the UPC agreement enters into force. The status is unchanged in Great Britain, Spain, Poland and Turkey since these countries are not UPC members. But in the UPC member states of this family; Finland, Sweden, Germany, France, Austria and Italy, the start of the UPC system has shifted the national patents under UPC jurisdiction, although they also still remain under national jurisdiction. These countries have therefore been marked with striped colors.

The proprietor of the patent family in figure 8 can file an infringement lawsuit with the Unified Patent Court if infringement takes place in any (striped) UPC-country. The decision given by the UPC will then have legal force in all striped countries. Alternatively, the owner could file separate infringement lawsuits with the national authorities in some or all of the striped countries. The same options are available to a competitor who wants to invalidate the patent family. As before in figure 5, neither the proprietor nor the competitor has any choice when it comes to Great Britain, Spain and Poland: only national legal actions are possible in non-UPC countries.

OPT-OUT requests can be filed also for national patents created in UPC-countries through EP validation before 2023. An OPT-OUT request moves the patent family from figure 8 back to the initial state which was illustrated in figure 7. An OPT-OUT can be useful to the patent proprietor because it forces competitors to challenge the national patens one by one if they seek to invalidate this patent family. As mentioned above, proprietors can cancel the OPT-OUT if they at some point want to file an infringement lawsuit with the UPC.

Summary

It’s important to remember that all changes discussed above apply only to European patent applications filed with the EPO and national patents which have been created from such applications through EP-validation when they were granted. The changes do not concern patents granted by national patent offices such as Finland’s PRH. A patent granted by PRH will therefore never come under the jurisdiction of the UPC, but a European patent which was granted by the EPO and then validated in Finland will be under the jurisdiction of the UPC unless the proprietor exercises the OPT-OUT.

The new system has its advantages (the unitary patent covers a broad geographical area at a relatively low price), but it is certainly not any simpler than the old system. It’s a good idea to consult a patent expert when weighing the benefits, drawbacks and costs of the unitary patent and OPT-OUT decisions.

Don’t hesitate to contact Boco IP’s patent attorneys if you have any questions about the unitary patent, the UPC or European patents. We are happy to help!

Thomas Carlsson is Boco IP’s partner and member of the board. He published the book Good Patent Applications in 2021

Latest blog articles

Leaders League has recognized Boco IP as the Best IP Advisor in the Nordics for 2024, awarding us the esteemed Winner Award

Coverage of Unitary patent improves

Boco IP celebrates multiple rankings in IP STARS 2024

Eight of Our European Patent Attorneys Featured in the IAM Patent 1000 2024